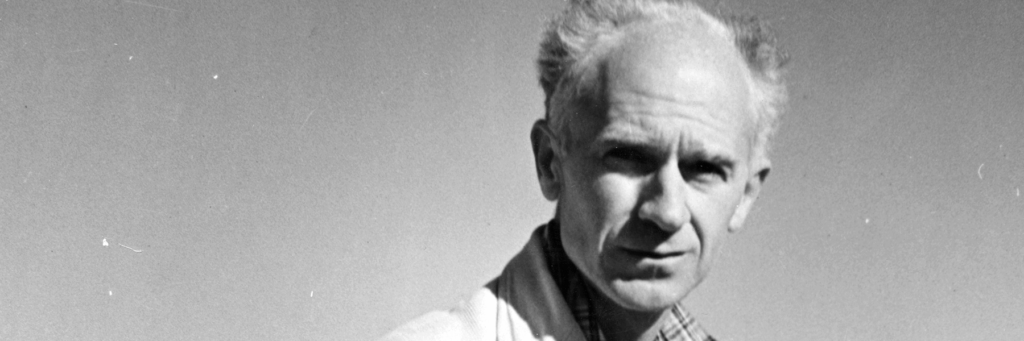

The war torn faces of the everyman earned him a Pulitzer Prize before he was gunned down in the battle of Okinawa. This is the life of war correspondent Ernie Pyle, who stormed the beaches of Normandy with a notebook, and how his exploits serve as a partial character inspiration for the main protagonist in my upcoming novel, Liberation.

Pyle, better known as “Ernie” to all who knew him well was a distinguished journalist and foreign correspondent thrust onto the front lines following the Fall of France to the Nazis in 1940. Unlike war reporters who served as enlisted infantrymen, often reporting for the famed Stars and Stripes paper, Pyle was a seasoned journalist who captured the horrors of war as would a novelist.

Ernie Pyle hails from Indiana, and dropped out of college to pursue a career in journalism, where he later joined the upstart paper, The Washington Daily News. Pyle’s early reporting focused on the booming business of aviation, where Amelia Earhart once said, “any aviator who doesn’t know Pyle is a nobody.” Keen for adventure, he travelled the United States and the Americas in search of the human interest stories nobody else would cover. He covered stories of everyday life during the Great Depression, and gave voice to the Greatest Generation, a theme which would continue across his war reporting.

Pyle initially reported from London in 1940, covering The Battle of France and the lead-up to a world at war. He first arrived on the front-lines in 1942 during the North African campaign, where my own grandfather Joseph Deegan served as a Captain, including during the 1943 Battle of Kasserine Pass — a battle which saw heavy American loss due to the superiority of German military equipment under the notorious Erwin Rommel. It was an eye-opener of the brutality to come, but the Americans regrouped and repelled this Axis victory; my grandfather was promoted to Colonel. My grandfather later married my grandmother, a nurse lieutenant, in a small ceremony in a French Catholic church in Tunis, Tunisia. He departed for Italy shortly thereafter with the bulk of the American war effort, Pyle in tow.

It was in Italy in 1944 that Pyle wrote his most famous piece, about the “dog face” soldier, arguing they should receive combat pay similar to the allowances provided to airmen of the time. That piece won him a Pulitzer Prize, and Congress later passed “The Ernie Pyle Bill” authorizing combat pay for infantry men, a law that still exists today.

Following the Italian campaign, Pyle re-grouped with Airborne troops in England to depart for Normandy during the D-Day invasion. This is his recollection of that momentous event, which he dubbed “the miracle on the beach.” He would go on to write three columns on the invasion, before continuing on with the offensive, telling the stories of US infantrymen in great detail as they would eventually go on to liberate Paris, which he detailed in his piece, Liberating the City of Light.

Sadly Pyle never saw the enduring efforts of his work beyond World War II, as he died under heavy fire during the battle of Okinawa. His legacy is immense, and his influence still felt among those who would follow in his footsteps, like foreign correspondent Joseph Galloway, famed for his book We Were Soldiers Once … and Young: Ia Drang – the Battle That Changed the War in Vietnam. Museums were erected to preserve his work, and an award was named in his honor, “The Ernie Pyle Human-Interest Profile Award” granted to exceptional war correspondent’s ability to emulate his style.

What began as a writer finding his way led to a great storyteller that immortalized the contributions of the Greatest Generation in the ultimate battle of good v. evil; he told stories not only of liberation but of the personal battles all of these heroes fought. An immense figure in American history, an enduring legacy of words at war, Ernie Pyle’s work represents the power that exposition has to change the world.

Discover more from MK Leibman Writer

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.